Overpriced rounds, a late stage VC bubble, and Sarbanes-Oxley are killing VC, investors and founders, as well as worsening inequality.

Institutional Investment in Late-Stage Venture Capital: Navigating Perverse Market and Regulatory Dynamics

Institutional investors’ sustained interest in late-stage venture capital (VC) funds is shaped by a complex interplay of behavioral, economic, and regulatory factors, despite these funds often underperforming relative to benchmarks such as the S&P 500 (see part I of this series). In this part II, I’ll examine the impacts of psychological biases, economic incentives, regulatory changes, liquidity preferences, and the evolving market dynamics that drive institutional capital toward late-stage ventures regardless of cost.

Institutional investors are often drawn to late-stage funds and the companies they back due to perceived lower risk, attributable to their established business models and proximity to liquidity events like IPOs. There is a lot of bias and false beliefs built into this system, and it has become toxic. So let’s break down what’s going on, and why allocators are funding this way.

Psychological Biases and Market Dynamics

Behavioral finance principles, such as the familiarity principle, herd behavior and the sunk-cost fallacy, are extremely relevant to investment decisions and play an outsized role in decisions to invest in late vs. early stage VC funds. Let’s cover these first.

The familiarity principle ensures that the known quantities—established companies nearing an IPO—seem safer than less predictable early-stage investments, even if they don’t provide investment returns that are positive after risk adjustment relative to the S&P 500. Because you’ve heard the names Stripe, WeWork, OpenSea, Brex, you are inclined to invest in the thing you’re familiar with, and the funds that back them. That can be a bad assumption when WeWork is the one you back.

The perceived safety of herd behavior (AKA, the bandwagon effect), wherein institutions follow the investment leads of their peers, is misleading. The assumption that the crowd knows best can also be viewed as a fear of missing out on potentially profitable opportunities. No one gets fired for following the market, so playing it safe with the pack is a reasonable strategy. Unfortunately, this is how lemmings go off cliffs.

The sunk-cost fallacy is another cognitive bias that leads many allocators to continue investing in a fund because of the time, money, or effort they have already committed, rather than cutting their losses. The rationale is often that not continuing the investment would mean that the initial resources were wasted, even though continuing does not necessarily lead to a recovery of those sunk costs.

The combined effect of these three biases are beginning to be apparent when you examine flows of capital into late-stage VC funds, with LPs going along for a “ride” that seems stuck in neutral. Moreso, it may also be that allocators have lost the ability to underwrite technology, human resource, and execution risk, and are now only willing to underwrite market risk. Consider the following charts:

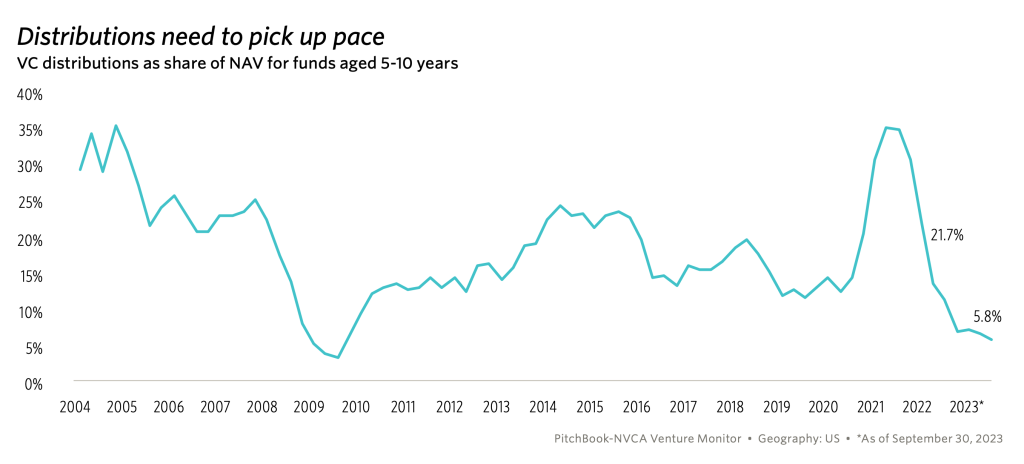

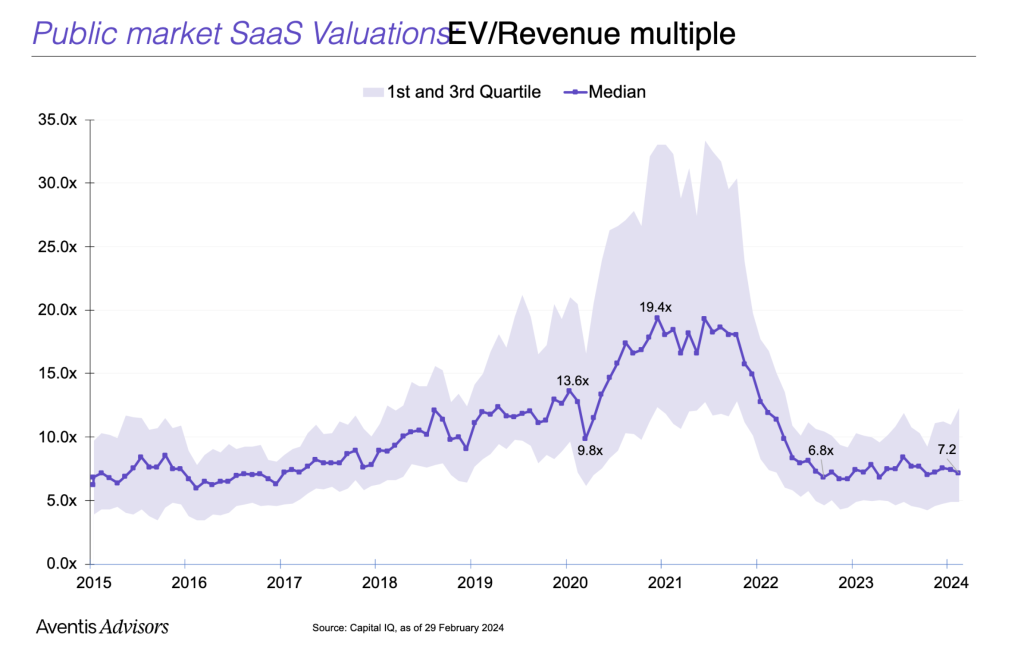

Distributions are at record low for a non-recessionary period, because overpriced deals over the past four years can’t be off-loaded to public markets. After pricing SaaS deals at 20x revenue just three years ago, you have a stupid amount of growth required to reach the same valuation at 7.2x revenue. Today’s valuation multiples aren’t low either, they are average for fundamental analysis based upon discounted cash flows weighted for a reasonable cost of capital in our current rate environment, unlikely to change and more realistic than the free money of the past decade.

As a result, late stage VC funds are writing larger checks to existing portfolio companies at higher and higher valuations to keep them afloat (if they’re still losing money) or in a ponzi scheme effort to keep over-marking up the winners to offset the losers. Worst of all, by delaying exits, they are not providing exit liquidity to their LPs and thus replenishing the VC funding cycle. According to JPMorgan in the Pitchbook NVCA 2023 Venture Monitor, “for vintage years 2013 to 2019, over 50% of the total value in venture funds relies on existing positions.”

Because late-stage VCs can’t IPO today without taking losses on their portfolio after writing big checks at massively inflated valuations, “unicorn” hold times increase beyond fund timelines.

What sustains this cycle is LPs willingness to keep pumping money into the late-stage funds so they can continue their sunk-cost fallacy investing on valuations not subject to public market scrutiny. Again, no one wants to recommend the “riskier” emerging manager at a small fund when the so-called experts at name brand funds are struggling to perform. Familiarity and herd bias alert!

As a result, early-stage VC is getting crowded out. The share of early-stage VC deals between $5-10mm has shrunk by 2/3. LP funds available for early-stage VCs continue to shrink. According to data from Crunchbase, 84% of capital raised by U.S. venture investors went into funds raising $250 million or more in 2018, and has increased every year since then according to Pitchbook data. As a result, VC funds managing $250m or less now account for less than half of all VC capital raised, down from over 75% in 2013. In the first two quarters of 2024, just two funds, Andresson-Horowitz and General Atlantic, raised 44% of all the venture capital raised by all VCs (Pitchbook).

While I have no data to support a hypothesis that allocators have lost the ability to underwrite technical, human resource, and execution risk, it’s clear that they are not underwriting these from the checks they’re giving VCs. Given that they only appear to be willing to invest in market risk, it seems bonkers that they do so without liquidity. You can better manage market risk in public equities with liquidity, so why do VC at all (and we’re back to part I).

This trend also shows in absolute dealmaking numbers collapsing for early-stage VC. According to AngelList, the second quarter of 2023 saw the lowest rate of early-stage startup dealmaking in the history of their dataset (dating back to 2013).

If you read part one of this series, the irony of the situation is that the VCs who continue to generate the highest returns are having the hardest trouble getting capital as late-stage VCs hoard assets and LP money. Until late-stage funds provide LPs liquidity via exits, the cash that feeds the whole ecosystem is locked up. Those exits are not likely to come soon.

Late stage VC is poisoning the well for the whole industry.

So why don’t early-stage VCs just work with founders to bypass the late-stage fiasco and encourage their portcos to go public after their series A/B rounds like we used to? Well, Congress kind of messed that up for everyone.

Impact of Regulatory Changes on IPO Timing

After the Enron scandal (which someday I’ll write a very cool post about but SoxLaw has an excellent summary here) Congress needed to show voters that they were going to do something about corporate fraud. In typical government action, they acted without fully considering the consequences of their actions. Surprise! Government is as ignorant as it is incompetent.

The resulting Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 had a profound impact on the public offering landscape by dramatically increasing the cost to be a publicly traded company, imposing stricter financial reporting rules, forcing companies to hire more auditors to audit the audit (yes, that is as crazy as it sounds), and dramatically escalating governance standards for public companies.

In summary, Congress decided to stamp out fraud from corrupt auditors by adding even more auditors and creating additional byzantine governance systems for them and corrupt managers to hide in. Yes, that makes no sense.

I’ve looked at a lot of academic research to see if SOX actually reduced fraud. Without going into too much detail, it hasn’t. The best paper I can find on the topic shows that SOX only reduced the “probability” of fraud by about 1%. However, it did dramatically improve the detail of reporting provided to the public. Let’s not minimize that, and yet I’m hoping that Adam Packer will do a brilliant analysis to see if this resultes in improved investment manager performance -likely not, but surprise me!

So while SOX did dramatically improve information reporting and volume, fraud has not really decreased, valuations are down, and companies have to delay their IPOs due to increased costs and expanded public-listing responsibilities.

The average cost for SOX compliance is exploding. According to Protiviti’s annual SOX expense survey, on average, companies allocate $1–2 million for their SOX budget, with internal audit teams dedicating an additional 5,000–10,000 hours annually to SOX programs.

According to Protiviti, the average SOX compliance cost in 2023 was:

- Companies with more than 10 locations: $1.6 million

- Companies with only one location: $704,000

- Companies with $10 billion or more in annual revenue: $1.8 million

- Companies with $500 million or less in annual revenue: $651,000

When you have to shell out $1-2mm for one compliance cost, plus heaven-only-knows how many thousands of hours of additional internal audit time, you can’t go public until the economics make this massive cost immaterial.

As a result, since SOX passed, the average time from founding to IPO has notably increased—from about 5 years in the late 1990s to more than 10 years recently (Pitchbook data, thank you once again). This regulatory-induced delay significantly affects the liquidity of investments, particularly those made by early-stage venture funds, extending the time to potential returns.

So, getting liquid on VC investing is more expensive and takes longer than ever. These are the primary reasons late-stage VC is so attractive to LPs. Despite poor performance, institutional funds have a strong liquidity preference, even if the private markets aren’t beating the S&P 500 (again, see part I).

Liquidity Preferences of Institutional Investors

Given the extended timelines to IPOs, late-stage VC funds have become more attractive due to their shorter duration from investment to exit. While I can complain all day about extended unicorn hold times, the hold times are still longer if you invested earlier. Institutional investors, including pension funds and endowments, prefer investments that align with their liquidity timelines. Late-stage investments generally offer a quicker path to liquidity, matching the large pools of capital that institutional investors need to deploy efficiently.

So when average VC hold time is approaching ten years AFTER becoming a unicorn, who wants to invest in the early stage VC who backed them six to seven years before then (CB Insights, State of Venture 2023). Seventeen to twenty years is a very long time for an institutional LP to hold a private security, so who can blame them!

While I can find no solid economic research to explain why institutional investors would favor late stage VC on the basis of liquidity preferences alone, it stands to reason that a 17-year hold period is not acceptable for most funds of any size to get liquidity at any cost.

The Necessity of Large Capital Pools and the Impact on Founders

The growing average market cap of companies at IPO—from around $500 million in the early 1990s to over $2.5 billion today—requires larger rounds of late-stage funding. As companies grow larger and remain private longer, they need substantial capital to scale up to absorb the costs of a public offering post-SOX. This need makes large late-stage funds particularly appealing, as they are capable of mobilizing the capital required for continued growth. However, this trend has profound implications for startup founders, who often endure increased dilution and a loss of control as they raise more capital under increasingly stringent terms. The loss of control has real impact, as TechCrunch recently reported that VCs are using this power to block IPOs and prevent founders from liquidity. This leads to strategic misalignments that might endanger long-term success.

The assumption here by VCs justifying their control provisions is that the late-stage VC funds provide better oversight and governance and will better protect investor interests on behalf of their LPs. Really? Are VCs better and smarter than public markets and their oversight? I doubt it.

Again, I have no research (and I doubt you could put together a credible quantitative analysis), but I think it stands to reason that thousands of public investors and a public board of directors do a better job of oversight than a handful of privileged insiders who fundamentally share the same world-view as VCs. Yes, we have group-think and bias too, so better off if more eyes can see the business.

The closest thing I have to a benchmark on this is to see how company valuations change post-IPO, when public scrutiny provides the best check to the opinions of private company valuations and the ability of VCs to provide good oversight and valuation guidance. And yes, when you look at the sheer number of unicorns falling from grace since 2022, it would appear that the private markets overpriced and misgoverned significantly (see Techcrunch and Hurun).

A final note on this, if you want to nerd out on great IPO data, check out Jay Ritter’s recently updated data here. It rocks.

Diseconomies of Scale and Risks to the Ecosystem

The preference for large funds and substantial capital injections can lead to diseconomies of scale, where the size of the investments begins to detrimentally affect fund performance. As suitable investment opportunities become scarcer, funds may end up deploying capital in less optimal ventures, with more funds bidding up the price for available assets. This, in turn, can dilute returns. Moreover, as founders lose equity and control, the risk of misaligned interests increases, potentially affecting the company’s strategic decisions and long-term viability.

The larger the fund, the greater the challenge in deploying capital efficiently, which often results in decreased returns and increased risk of strategic misalignment within funded companies. Ouch.

Conclusion

Institutional investors’ preference for late-stage venture capital funding is dictated by a blend of psychological biases, regulatory impacts, liquidity preferences, the loss of their ability to underwrite anything except market risk, and the structural requirements of modern IPOs. While these investments may offer the perceived safety of shorter time horizons and reduced risk, they come with their own set of challenges, including potential misalignments and increased founder dilution.

The situation was made worse when the 2021-22 market bubble caused late-stage funds to overprice investments, and now extend exit periods so that they can avoid going public at a loss. Without exits, no new liquidity is flowing back into institutional and large family office LP investors, so early-stage VC funds are getting squeezed with fundraising for new funds that have ever elongating exit strategies. This, in-turn, creates less companies getting funded to their series A/B, and further restricting deal flow for late-stage funds, thus exacerbating their crisis to allocate capital and double down on their already overpriced, current portfolio companies.

So how do we break this doom-cycle? Part III coming soon…